On the evening of 12 November 2019, photographer Patrizia Zelano witnessed the devastating news that one of the worst floods had struck Venice. Early the following morning, she set out from her home in Rimini, drove north-east for two-and-a-half hours, parked on the mainland, and ultimately arrived by rail in the battered city, which was still in emergency.

As a result of a confluence of circumstances – a sirocco wind tide topped off by a full Moon tidal high point and a quickly traveling cyclone – the sea level was up 1.89m and 85% of the city centre had flooded. Only the record-breaking 1966 Acqua Granda, which initially brought the world’s attention to Venice’s survival problem, rivaled this disaster.

During her two-day excursion, Zelano rescued 40 books. While most are now beyond reading, her images of the destroyed books chronicle the vulnerability of the lagoon and its cultural patrimony – and a drive toward potential solutions.

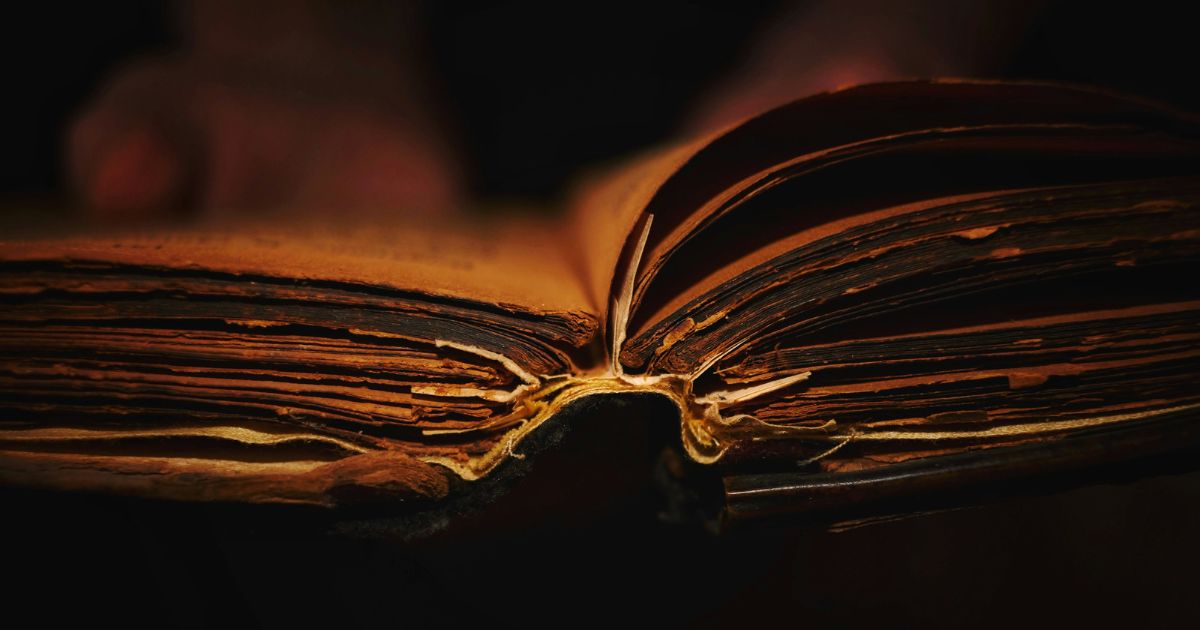

With rubber boots on her feet, Zelano waded from the train terminal down Strada Nova, which was still roughly 40cm (1ft 3in) under water. She had gone to the home of a friend of a friend. The tide had receded by then. “All kinds of objects, bits of furniture, chairs, were heaped up, like rubbish, everything was utterly soaked,” she explains to the BBC. While the owners were working on salvaging what they could, Zelano concentrated on their books, which seemed to her lovely in their rot and metaphor. One of the books from the house (the one above) resembles “an archeological find from the Stone Age,” she states. “It doesn’t open any longer; it’s cemented.”

Zelano concluded that she must rescue more books. She telephoned Lino Frizzo, a Venice bookshop owner, whose shop is appropriately named Acqua Alta, “high water”, the Venetian description of floods. Frizzo just informed her that, due to the frenzied activity of the days concerned, he doesn’t recall that she was present. With his staff, they worked day and night cleaning up and salvaging the inventory. They donated Zelano books past saving. These were mostly from the early 1900s, which in Italian and Venetian terms is old but not antique. They were lovely, though, such as this poetry book that had a rich red cloth cover. “A hurt book,” says Zelano.

Zelano had 40 books and placed them in large black plastic bags. At 55 years old, she was traveling alone on this mission. “No way I could haul them all myself, and it was difficult to get people to assist.” She hailed a gondoliere on the canal and persuaded him to row her back to the station in a gondola. “Some of the books, such as this one, would break apart at the mere touch of my fingers,” she says. “You notice the hole to the right.” She says this specific volume appears delicate, like lace, and one day would love to get into the fantastical words the pieces of several pages pressed together have made. In her studio at home in Brooklyn, Zelano, who had studied with Italian photography master Guido Guidi, photographed the books in natural light only. She didn’t even open them, but left them just there as they were. This one was a 1949 Treccani encyclopedia. “I like that [on the top right-hand corner] you can see the figure of a genie, a Pagan figure. It’s the Genius of the Catacombs of Domitilla in Rome, who is a protector, and that is comforting to me.”

The form of another Treccani volume of 1951 recalled sea waves. Moments such as the 2019 are bound to occur more and more frequently due to rising sea levels and subsidence of the city. With these images, Zelano aims to build “a eulogy to culture, to our history. They practically enshrine cultural memory, universal knowledge. So, there is loss. But with this photograph, there is healing, and there is also resistance”.

“This book is crying. You see the tear?” says Zelano. The encyclopaedic book was still wet when she snapped the photograph, so wet in fact that a drop of water can be seen in the front. Its form is a metaphor of the tidal action of the ocean. In 2024, global sea levels increased by approximately 5.9mm (0.23in) per year, says NASA, although rates differ in various oceans. Also, Venice is losing about 1.5mm annually due to land subsidence.

“I organized these books and they resemble waves, or letters written on paper, or you see heart shapes,” says Zelano. She wishes she had been able to carry more books home. “When we go through personal or environmental storms, we know what we need to rescue, that is, what is essential to us.”

These art history encyclopedias of 1978 present the paintings of the legendary 18th-century Venetian painter Canaletto, who depicted the most popular views of the city. Since the devastating floods of 2018 and 2019, Venetians welcome floods as part of their lives during autumn. But they realize that the city’s Mose tidal flood-defense system, regulating the tide, is only a palliative measure.

“Photography is essential because it can testify, but also, in turn, trigger something different,” explains Zelano. “It suggests new ways of thinking, new views. Mine is a symbolic piece, designed to provoke thought. A photographic memory, where photography saves knowledge and turns destruction into hope and meaning. It is a way of awareness intended to bring solutions.”